AntiFragile Learning in Times of War

I am Ukrainian.

My life has changed significantly since the new active phase of the russian war against Ukraine began ten months back.

In truth, the war started eight years ago, but this new spiral of russia’s madness has brought turmoil on an all-new scale, and has begun to destabilize the entire world.

The past ten months were awful for me and for a lot of Ukrainians. Many friends in end-of-the-year resolutions mentioned that it was the worst year of their lives. Sadness, anger, anxiety, fear for our families and friends...not to mention the loss of those same friends and families, our homes, and our sense of safety. This is a typical mixture of feelings for Ukrainians in 2022 and 2023. I’ve personally experienced most of it as well; missiles have struck near my house, but I’m fortunate enough to have not lost any family members.

I’m also a practitioner of modern approaches to managing knowledge work, sometimes referred to as agile (software) development and business agility. One of the key crucial practices of management in complex environments is reflecting back on your experience in order to learn and grow. I wouldn’t wish the experiences of the typical Ukrainian upon anyone, but even very unpleasant experiences could become valuable learning.

So I’ve taken the time to reflect upon my own experience and squeeze some learnings out of my past year. Many of these observations have parallels to agile. Some may seem obvious, and others may surprise you.

Peer Pressure and Alignment

I’ll admit to being wrong about a few things before this new phase of the war, but the toughest part of it was learning I had the wrong impression of people on the other side.

Right before the February 2022 invasion, despite multiple signals from the intelligence services of allied countries, despite the army waiting in russia and belarus, I still didn’t believe russia would invade Ukraine. I thought that the worst of what could happen was an escalation in the East of Ukraine—in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions, where we have already been at war for eight years. My main reason for thinking so was a belief that, in the case of a full-scale intervention, mass anti-war protests would take place in russia. Not hundreds or, maybe, thousands, but millions of people. And if those protests took place, it would of course, be impossible to continue the invasion. My parallel to the agile world is a pretty well-known and widespread term, mostly applicable in the context of teamwork: “peer pressure”.

The term may have some negative connotations (for example, in a schoolyard), but in a team or workplace, peer pressure can be helpful in terms of holding people accountable to their commitments. Team members sharing their opinion on your work, your decisions, and so on, can lead to reflection, growth and better decisions in the first place. In the case of a country, of course, peer pressure is also possible. Nobody would or could do something that opposes the will of the majority of the population...or so we thought.

We, Ukrainians, have personal experience with how effective peer pressure can be from two recent revolutions: in 2004 and 2013. So how wrong I was. There were very few anti-war protests in russia—at the beginning of the war few occurred, with 2000 people attending the largest protest... in Moscow, population 10+ million. By the end of March, the protests had almost vanished entirely. So yes, there were some voices against the war. I know russian support for the war is not 100%. But those who are willing to stand against it are a minority, insignificant compared to the total population. The vast majority of the population seem pretty much aligned in their views, supporting the war. The hardest part of it was realizing that the people supporting the war are not just some abstract people but your friends, people you worked with, and a highly intelligent crowd engaged in knowledge work. So, no peer pressure and very good alignment, just towards what I consider the wrong goal.

Another related, well-known metaphor is that of the frog in the pot of heating water, not jumping out until it’s too late... Free speech, civil rights and other issues have worsened in russia over the past eight years, but citizens tend to normalize all the time (it’s not great but still okay, not going to get worse...) which has led to where they are today.

Actions speak louder than words. Always. We know that about agile. Only by interacting with your environment (actually doing something) will you be provided with feedback. Planning is important, but without actions it’s only words.

Actions allow us to quickly clarify who is who and what is what. When Ukraine entered crisis mode (starting February 24, 2022) there was no time for softening things. In the face of (what was for us) an existential crisis, it was necessary to get clear fast on other people’s personal stance, values, etc. Those tough questions/ discussions either happened quickly or, in some cases, were not even needed because position/stance was clear from actions. So how you operate and what you do in a crisis can tell more about you, your values, and your principles rather than a lot of “talking” in the previous/normal environment.

Accountability / Responsibility is Also Known as “Not My Problem”

This is one of my favorite learnings/observations. I’ve been unfortunate to see this too many times within organizations—when some “grey” area of responsibility is recognised but avoided by everyone nearby. Nobody is willing to take on more work when it is not fully expected because of their position, rank, or some other formal, structural reason. That might become even more of an issue in times of change when things are least static and fluid. When discussing the problem with somebody you may hear something like “Yes, I see your point and even support you in this, but what can I do—it’s not my area of responsibility. You should talk to John, if he’s on board we would make it happen.” Overall, as an organizational coach and consultant, when I hear “not my problem” I recognise it as a special flag or trigger to pay attention and dive deeper. While this ping-pong of responsibility avoidance happens sometimes in organizations, it is also (usually) easy to (relatively, depending on size) locate somebody ultimately responsible for the subject matter.

“I’m not supporting the war, but what can I do about it?”

became one of the excuses I’ve commonly heard from russians. Their logic is that fighting against the conflict doesn’t make sense because they will just get arrested and that won’t change anything. So they are against the war, but only in a way that won’t get them in trouble. I’m not stating that all russians are guilty, of course. However, all russians are responsible for it, and those not actively fighting against the war are showing avoidance, even rejection, of responsibility for what is happening in their own country. The absence of a decision is also a decision. Such a passive-aggressive position shows actual support for what is happening. With positions like this being so common, it is not strange that putin has remained in power for two decades.

In an organizational context, this sort of avoidance could be fixed with several coaching sessions. In a country context, assuming responsibility is much harder and may take much longer. Immediately after WWII, Germans felt injustice, humiliation, and oppression. It took one generation to accept responsibility... But you should talk to John, it’s not my fault...

What is “Normal”? Speed of Adaptability

A few things became clear to me quite quickly after February 24. The first one relates to norms and understanding what is considered to be “normal.” Things you could never even imagine happening in real life become commonplace. Killing civilians, raping, torturing, and destroying civilian infrastructure. Bucha, Mariupol... There is no way you could unsee it or ignore it—it just happened. This causes your definition of norms to shift as well.

My second observation is about the speed of this process. I was shocked at how quickly this understanding could shift and change. What was unspeakable literally a few weeks ago became normal now. What is unspeakable now, will be our “normal” in one month.

Rocket attacks on the capital and other cities of a European country were unspeakable, and now people are used to working from bomb shelters. Not having electricity available countrywide was unspeakable, and now people are used to power banks, generators, and so on. People are quickly adapting to changing environments. Again, I would clearly prefer this not to happen, but it is happening. We could learn from it.

So the next time somebody makes a statement that <something> is too much of a change and will push the organization too far out of its comfort zone—I have all the internal assurance I need to continue challenging it.

Horizons of Planning and Decision-Making in the Chaos

This observation might look obvious but is an important one (and also a pretty uncomfortable one). After February 24, the world changed significantly and a lot of our old plans became irrelevant. In addition, the act of planning itself changed. First, all long-term planning became hard and sometimes impossible. Second, even sensible shorter-term plans needed to be updated very frequently. It goes without saying that the complete (or close to that) absence of planning doesn’t contribute positively to psychological safety, which is our next point.

You may remember Dave Snowden’s Cynefin (Clear-Complicated- Complex-Chaotic), and that in a Chaotic state you Act->Sense->Response.

In order to get out of a Chaotic state as soon as possible, leaders need to act. In these cases, doing something quickly might be way better than taking time to consider and think about what is the best course of action.

Psychological Safety

For agile practitioners, the importance of

psychological safety for team building and achieving desired results is a well-researched field. There’s no need to explain how, after all the terrible war crimes committed by russian soldiers in Ukraine, that the psychological situation for many Ukranians has suffered and many have had to leave the country in search of safety. For now, it is hard to estimate the scale of the problem and what effect it would have over (possibly) many years to come.

Self-Organization and Volunteer Movement

Most Ukrainians participate in this war in some or another way. Generally thinking, I could break it down into three big categories (some people might contribute to a few of those categories at the same time).

The first and most obvious one is serving in the army forces. The Armed Forces of Ukraine are the reason why Ukraine still exists. The second one is very interesting. It is a volunteer movement, a decentralized network of individuals and NGOs that find, buy and deliver whatever is missing/needed/ required for the army and civilians. This whole movement formed in 2014 when the war started in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions. By that time, our armed forces were not supplied at any suitable level—they needed a lot. Volunteers were supplying them with necessary equipment. Without this network, Ukraine wouldn’t have survived back then, and we won’t survive without it today. It took some time to learn how this could be done, to establish rules and agreements for work, and carry out collaboration with other such organizations and official entities. This distributed network of self-organized individuals, who are (in most cases) not paid to do this, is somehow similar to the open-source movement, and looks really close to what real agile might look like.

The third way of being helpful is continuing to work, keeping the economy alive and donating to armed forces to bring our victory closer and closer. Just a few illustrations of this I’ve seen recently: a group of IT folks (product people, designers, developers, etc) created a fund that specialized in high-tech help for the army, called KOLO. Individuals and organizations are welcome to donate periodically, which I call donation as a service (DaaS). Another example: the CEO of an e-commerce startup is raffling his luxury German car to help the army. Even a small donation got you a chance at winning, which in the end collected eight times the cost of the car. A final example is a Ukrainian former two-times NBA champion, selling on auction his NBA championship rings to help reconstruction after the russian attacks. Everyone helps in this or another way.

A few paragraphs above I made a point that decision-making in the fog of uncertainty is challenging and clearly changes the horizons of planning. Another angle related to this deals with longer-term planning and looking into the future. This is not the strongest analogy from a logical perspective, but it feels similar from an emotional perspective. As you know there is no predefined end-state for an agile or digital transformation. There might be direction, there might be some goals, which are likely to emerge along the way...

Likewise, it currently feels as if there is (almost) no way to finish this war. Obviously, it is unlikely that an unmotivated and unskilled russian army could conquer Ukraine. Theoretically, they could turn Ukraine into a nuclear desert, but that’s theoretical (nobody knows if they even have enough, or any, fully functional nuclear weapons). However, the Ukrainian “win” is also very blurry... Yes, with the continuation of help and support with weapon supplies from Western partners, it is possible to knock the russians out of Ukrainian territory, including Crimea. But that will not end the war. Nobody believes that expelling the russian army from Ukraine will last long. They will accumulate resources, regroup, and try again. Also, they could continue their terrorist missile attacks on Ukrainian cities from outside of Ukraine. Any “peace” agreement is not worth the paper it is written on or even the time spent in discussion. We all know it is not real. After all, every Ukrainian remembers the Budapest Memorandum signed by russia in 1994. The very first item on the Memorandum was about respecting the signatory’s independence and sovereignty in the existing borders. That was broken by russia in 2014. (In fact, I could write at length comparing this agreement in exchange for nuclear weapons, which now looks like a poor decision by Ukraine, and the agile manifesto value “Customer collaboration over contract negotiation.” These have similarities, as russia doesn’t value its contracts, only the power it can gain at any one time). So any “peace” agreement doesn’t make logical sense, as it won’t be worth anything.

This means the end-state is very foggy and unclear. I can think of only one (realistic) scenario to end the war.

You might have heard that in larger organizations, culture follows structure. This statement is known as Larman’s Fifth Law of Organizational Behavior.

I argue that, to change the culture and mindset that believes russia is a great empire that should control large portions of the world (and hold heavy influence over countries it doesn’t control), it must disappear as a singular entity. It should split into multiple, maybe ten or more independent countries (many of those still would have territory larger than most of the European countries or US states). In addition, none of those newly created countries should have nuclear weapons. I believe that a setup like that, over time, might change the current arrogant, imperial perspective, and in turn change culture. However, this collapse is possible only as a result of internal changes in russia, which I do not see happening. It’s a chicken and egg type of problem, and in the meantime, Ukraine suffers.

Just as you can’t choose your family, most of the time you can’t choose your neighbors. It wasn’t Ukraine that started the conflict eight years ago, or in February 2022. We all wish none of this had ever happened. We wish russia would just disappear into oblivion. Or that, nationwide, russia would experience a mystical change of culture and abandon all the habits and attitudes of the grand, conquering empire (actually disappearing into oblivion is a more likely scenario). Sadly, all of that is wishful thinking.

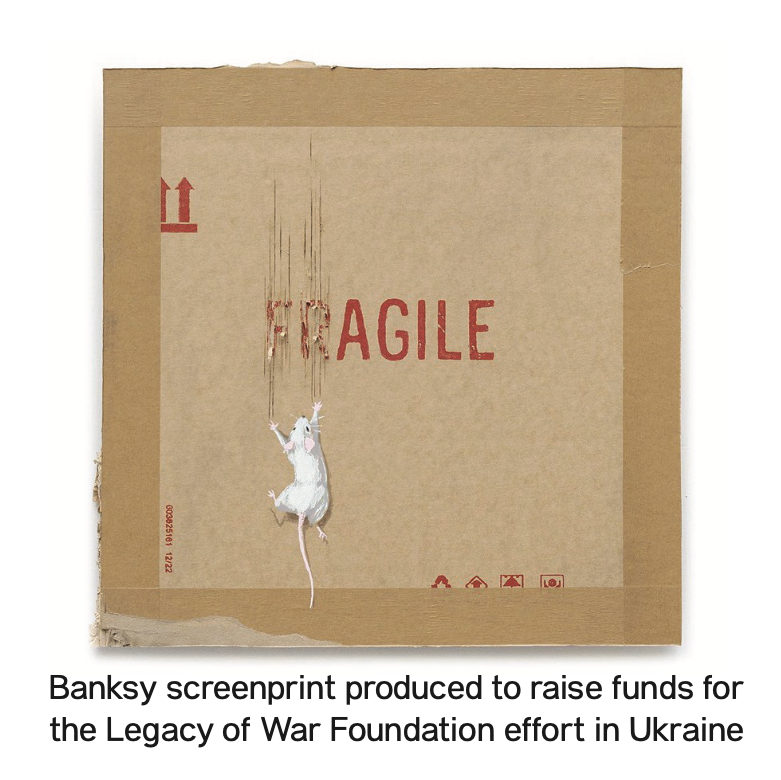

In closing, there is a great illustration by Banksy which sums up a lot of my thinking (which he is, by the way, selling to donate to Ukraine).

What was once fragile, under the pressure of a changing environment, could become agile and robust. Yes, we haven’t chosen this war, but we have to face it. Nobody else will do it for us.

As Dr. Deming, one of the grandfathers of change management, once said:

“It is not necessary to change. Survival is not mandatory.”

P.S. If you’d like to help Ukraine, I can think of a few things:

- Donate to the Kolo fund—I know them personally, trust them fully and send my donations there as well. You can find the Kolo Fund at koloua.com/en Please, donate.

- Stop any kind of economic connections

(selling to or buying from)

with russian companies. Please, check if your company is doing any business with russian companies. Please, do not contribute to an economy which is used to kill civilians. This is huge.

Editor-in-chief’s note: The capitalisation of proper nouns throughout this piece is an editorial decision by the author.

This content was originally published in the February, 2023 Edition of Emergence, The Journal of Business Agility. It has been republished here with the permission of the publication.

What is Emergence?

Emergence is the Journal of Business Agility from the Business Agility Institute. Four times a year, they produce a curated selection of exclusive stories by great thinkers and practitioners from around the globe. These stories, research reports, and articles were selected to broaden your horizons and spark your creativity.